Behind Unlimited: Playing With Experience

September 11, 2025 | Written by Tyler Parrott

One of the first big lessons a game designer is likely to learn is that players all have very different motivations to want to play. This is well documented in other trading card games that have identified different “player psychographics,” but it speaks to a larger point in game design: game designers don't just make products, we make experiences. After all, the rules and mechanics of a game aren't judged by some platonic ideal, but rather by how players feel when they play the game. Since our players are humans, and humans are emotional creatures, it's important for a game designer to think about the emotional experience we want to elicit in whatever game we're designing. This was something we discussed heavily during the development of Legends of the Force and its flagship Force token mechanic.

Iterations on the Force

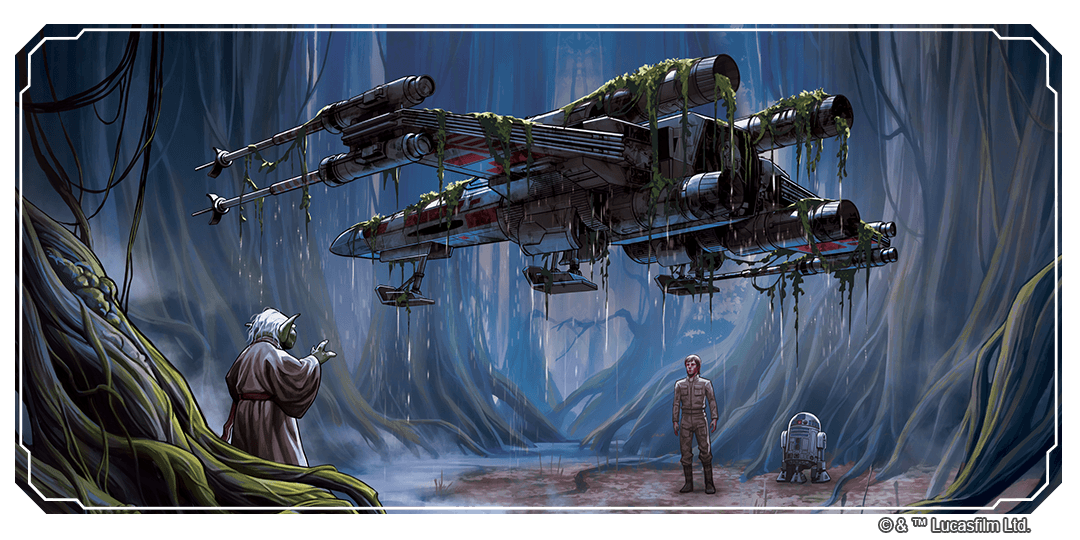

As I discussed in July's edition of “Behind Unlimited,” the Force token mechanic went through a lot of revisions. First it was a tug of war mechanic where only one player could have it at a time. Then it was a second resource players could accumulate incrementally. Then it was a binary resource that a player either did or did not have at any given time. In all three of these mechanics, however, there was a common assumption: that you would gain the Force by playing Force units. We want to reward players for progressing the game, and playing cards is one of the most basic game actions you can take. However, it resulted in undesirable incentives for deckbuilding. Specifically, it encouraged players to play with as many cheap Force units as possible and deterred players from playing expensive Force units. This made the more numerous early game cards even stronger while making the most powerful, exciting versions of fan-favorite characters—like Mace Windu (Legends of the Force, 149), Maul (Shadows of the Galaxy, 90), or Luke Skywalker (Spark of Rebellion, 51)—not worth playing in Force-mechanic decks. It led us to ask the question, “how can we make our sturdier, more expensive, Force units better at generating the Force?”

Simultaneously, we were trying to resolve how swingy the mechanic could be. Some players were able to chain Force generation repeatedly in a single round, resulting in dramatic and powerful plays, while their opponent struggled to get their engine to work because they didn't have the right cards at the right cost to make their effects work. So we tried a new idea for how the mechanic could work: if each player could only get the Force once per round, then we could more easily control how explosive the mechanic could be in its best-case scenario. And if it was dependent on controlling a Force unit at the end of the round, then we could make our more expensive and powerful Force units have value since they would be more difficult to get off the board than their cheaper counterparts.

This solved one problem but created a few more. You see, one of the other reasons that we were having trouble with the explosiveness of the Force mechanic is that the condition of “play a Force unit” provided no opportunities for interaction by the opponent. One of the pillars of Star Wars™: Unlimited is that we want this game to feel dynamic and interactive, that every action a player takes provides an opportunity for a counter-action from the opponent. Whether through the back-and-forth actions mechanic or the guaranteed one resource per round, we want the experience of playing Star Wars: Unlimited to be one of great agency. This is both a sense of agency in executing your own plan, but also a sense of agency in disrupting your opponent. The “play a Force unit” version of the mechanic prevented the opponent from having any agency in counterplay, as there's no easy way to disrupt your opponent from playing cards (hand and resource disruption are intentionally done at low volumes).

So the new version of the mechanic that gave a player their Force token if they controlled a Force unit now provided the opponent an opportunity to disrupt the Force engine. If a player could attack and defeat their opponent's Force units to keep them off the board, they would be able to prevent that opponent from gaining their token. But that counterplay would only work if a player was able to prevent their opponent from controlling any Force units, and Force decks would likely be exclusively made up of such units, so the only way to realistically disrupt the mechanic would be to prevent the opponent from controlling any units at all. Controlling no units is a horrible way to feel a sense of agency, so now we were actively encouraging players to prevent their opponents from enjoying the game as we wanted it to be experienced. Combined with the fact that it also took away the dream of getting to use multiple Force abilities each round, this solution proved to be a dead end.

Unlimited Foundations

As we kept hitting roadblocks in the design of the mechanic, we were simultaneously discussing a lot of the past card designs and how they did (or did not) achieve the experiential goals for the game line. In order to help facilitate that discussion, we highlighted how we wanted Star Wars: Unlimited to feel when playing in specific terms. Some of those highlights include:

- Players get to play with their favorite characters from Star Wars.

- A player rarely has to wait to take an action.

- When a player takes an action, they are presented with a variety of options to decide between (increasing in quantity as the game goes on).

- The game approaches a conclusion between rounds 6 and 9.

Something we noticed about the units we had designed in Year 1 were that there were a lot of cards with square or almost-square stats. This meant that games were naturally aggressive, as we had defaulted towards power-skewing our units, and also that units had trouble staying on the board because they were vulnerable to everything at their own cost point (and sometimes below their own cost point). There were very few 3 cost units that could survive an Open Fire (Spark of Rebellion, 172) and very few 2-cost units that could survive a Cloud-Rider (Shadows of the Galaxy, 210) or Battlefield Marine (Spark of Rebellion, 95). The units we had designed weren't necessarily weak, but because they weren't designed to be survivable, they…weren't surviving. This resulted in some undesired effects on the experience of playing the game. Specifically, it was going against two of the bullet points I mentioned above: players weren't getting to play with their favorite characters enough (because those units were being defeated too quickly), and players didn't have as many options as we wanted when taking an action.

At one point during the design of Spark of Rebellion, I ran an experiment. It was in the middle of a playtest, and we were seeing a lot of empty boards. Units would get played, and because they all defaulted to square or almost square stats (think 3-cost 3/3s, 4/3s, and 3/4s) they would very often trade with each other—one player would get in an attack at their opponent's base, then the other would attack the offending unit and both the attacker and the defender would be defeated. We weren't happy with the way the games were playing out, so I suggested a mid-playtest change: We would play the exact same decks again, but every unit would have +1 HP compared to what was written on the card. Suddenly, trades were much harder to do. Both players had less clarity on who was supposed to be attacking their opponent's units and on which units should be doing the attacking. The game was immediately a lot more fun, though it threw out a lot of the balancing decisions we'd made prior to that playtest. We got to see favorite characters stay on the board more often, and players had more options when deciding when and how to attack.

Now that was only an experiment, and while it did result in us HP-skewing our units a bit, it didn't drive us to a world where the default was that most units would be very survivable. But it was an experiment that we would remember a couple years later when it came time to develop Legends of the Force, and we were finding ourselves running up against similar concerns about the gameplay experience. So, as we were adjusting our development metrics to account for which cards from Year 1 were actually seeing play (which I wrote about earlier this year), we made a special effort to look at the lower-cost units and especially the survivability of those units. We wanted to make sure our two-aspect unique units were sufficiently more powerful than the single-aspect or non-unique units, and since that ceiling mostly hadn't been explored yet, this provided us an opportunity to develop a bunch of cheap units whose stats were specifically skewed towards survivability. Thus, a bunch of 2-cost unique units ended up as 2/4 units with unique abilities; Karis (Legends of the Force, 31), Yaddle (Legends of the Force, 45), Vaneé (Legends of the Force, 82), Gungi (Legends of the Force, 93), HK-47 (Legends of the Force, 130), Adi Gallia (Legends of the Force, 142), and Aurra Sing (Legends of the Force, 179) are all direct products of this reinvestment in the game's foundational fun elements.

The Control Conundrum

On the one hand, we were intentionally designing these highly-survivable units to give control decks more tools—if an early 2/4 or 3/5 unit gets to attack more often, they're more likely to generate card advantage if they're attacking lower-cost aggressive units that can't trade with them. But on the other hand, we were injecting into the metagame a huge obstacle for control decks. After all, control decks naturally want to prevent their opponent from having a bunch of units in play, since that's how they avoid losing, and we were intentionally making units harder to defeat. Control decks are a critical part of any healthy metagame (otherwise the fastest deck would always win), but they definitionally undermine many of the listed foundations for what makes Star Wars: Unlimited fun: they try to remove options from the opponent, they want to extend the game longer than we'd like, and they often are built around cards that remove units from the board instead of cards that represent exciting characters. So, we asked ourselves: how could control decks fit into the experience that we wanted players to have when playing Star Wars: Unlimited?

Our conclusion was ultimately founded on the philosophy of making control decks “slower” (in action economy) than they had been in the past. We had already seen some of this in the metagame with leaders like Cad Bane (Shadows of the Galaxy, 14), Bossk (Shadows of the Galaxy, 10), and Darth Vader (Spark of Rebellion, 10) who can deal 1 damage to a unit under certain conditions. Rather than designing more cards like Power of the Dark Side (Spark of Rebellion, 41) and Force Choke (Spark of Rebellion, 139) that could remove a unit in one action almost guaranteed, we would design more cards that did incremental amounts of damage so that a player could remove their opponent's units from the board, but it would require multiple cards and multiple actions to do it.

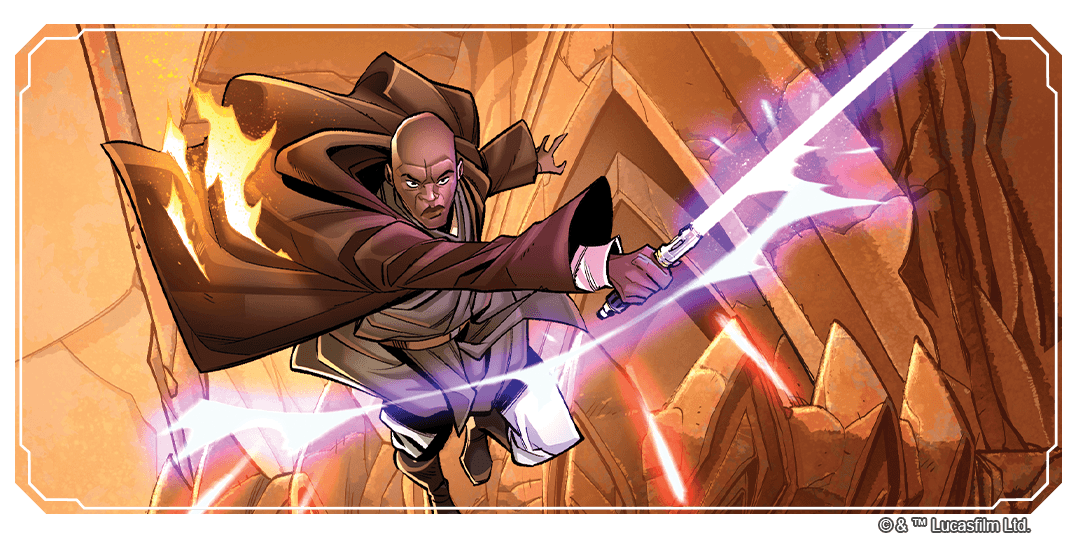

Additionally, we wanted to move away from our best removal being on events and towards our best removal being on units. Events are valuable because they can be straightforward and efficient, but they lack the excitement factor of a unit because they can't represent a player's favorite character. On the one hand, if our best removal was attached to units—whether through When Played abilities like Anakin Skywalker (Legends of the Force, 70) or Ambush like Maul (Shadows of the Galaxy, 90)—then control decks would still be full of fan-favorite characters. On the other hand, if control decks were playing units like Mace Windu (Legends of the Force, 149) and Ki-Adi-Mundi (Legends of the Force, 146) instead of events like Open Fire (Spark of Rebellion, 172) and Mission Briefing (Spark of Rebellion, 171), then those decks would naturally progress towards a victory condition just by nature of accumulating units on the board. A control deck full of events is liable to extend the game indefinitely, which runs counter to one of our experiential goals of Star Wars: Unlimited that it be a 15-20 minute game. Even a control deck that played removal units all the way up the curve—such as Death Trooper (Spark of Rebellion, 30) into Devastating Gunship (Twilight of the Republic, 36) into Anakin Skywalker into Darth Vader (Spark of Rebellion, 87) into Avenger (Spark of Rebellion, 40)—would naturally end up with enough power on the board by the time we wanted to end the game that they could just do it by attacking.

An example of what this philosophy might look like can be found on the leader side of Kit Fisto (Legends of the Force, 11). Kit's ability to deal 2 damage to a unit for 1 resource is extremely powerful and effective at removing units from the board, but it's still dependent upon the enemy units' HP values. He can easily take out the more glass cannon-y units like Jyn Erso (Twilight of the Republic, 143) or Sith Legionnaire (Legends of the Force, 81), while more survivable units naturally take longer for him to defeat with incremental damage. A Kit Fisto deck will still be able to deal with more survivable units, but it will look to combine his leader ability with other sources of damage—and the best source of damage is attacking with units. This means that a player facing a Kit Fisto control deck will still be able to play their units and probably even get to use them for a round, since it takes multiple actions for the Kit Fisto player to eliminate each one. The more we encourage players to use incremental damage (especially damage that comes from or requires units) to whittle down enemy units, the more we can make decks that control the board without taking agency away from their opponents. And since most of a control deck's cards would ideally be iconic Star Wars characters, they would also naturally have a way to end the game quickly once they had taken control of the board.

Dynamic Combat

Kit Fisto being an example of a more “Unlimited-appropriate” control deck brings us back to the dilemma we were attempting to resolve with the Force mechanic: how could we make the mechanic interactive, unit-centric, and give players a larger goal to pursue in their gameplay decisions? The answer, of course, was to lean into attacking with Force units as the condition for gaining the Force token.

This had some immediately apparent advantages. It meant that people were more invested in keeping their Force units in play, which meant they got to see their favorite characters on the table longer. It meant that more expensive Force units had a natural advantage of having more HP and therefore being more likely to attack multiple times to get the Force token (compared to their lower-cost counterparts). It meant that all of the game's natural points of interaction—attacking with units, removing enemy units from play with card abilities, and even exhaust abilities—interacted cleanly with the new mechanic so that there was plenty of counterplay. And it provided compelling sequencing puzzles as the mechanic subtly changed the incentives away from attacking with all of your Force units with back-to-back actions, in case you wanted to spend the Force token on a card ability in between. There was some internal consternation about the mechanic being too difficult to use if a player fell behind, but the way it reinforced the game's intended play experience was too effective not to keep.

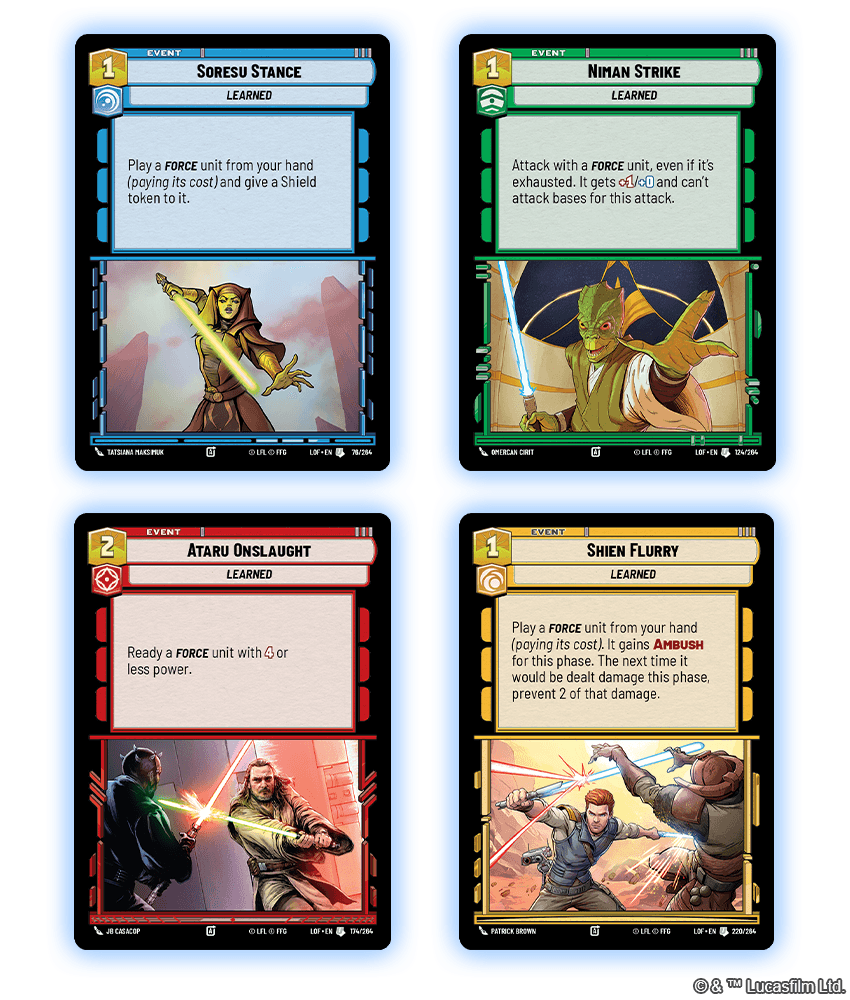

And to be sure, the concerns were valid. If the mechanic was only going to function if a player could consistently attack with their units, that created a huge incentive for the opponent to prevent that, especially by removing those units from the board before they got to attack. So while we were developing the set, we made a high priority to ensure that there were ample tools within the set to gain the Force token even if a player was struggling to keep a unit in play to attack with. Set designers Joe O'Neil and John Leo designed a lot of units (especially single-aspect Common units) that were geared explicitly towards being able to ensure they got an attack off. Sometimes it was by making units more survivable, such as Secretive Sage (Legends of the Force, 61) having Shielded or Witch of the Mist (Legends of the Force, 154) having Hidden, and sometimes it was by giving units Ambush so that they could attack immediately and gain the Force token for their controller, such as with Jedi Temple Guards (Legends of the Force, 113) and Mysterious Hermit (Legends of the Force, 208). Then, to compliment these common unit designs, they made a cycle of Uncommon events that helped players guarantee an attack with their Force units: Soresu Stance (Legends of the Force, 76) plays a unit with a Shield token; Niman Strike (Legends of the Force, 124) allows a unit to attack when it otherwise couldn't; Ataru Onslaught (Legends of the Force, 174) readies a unit to attack with its next action, and Shien Flurry (Legends of the Force, 220) gives a unit Ambush to immediately get an attack in.

What we ended development with was a new mechanic that overlaid perfectly onto the core gameplay loops of Star Wars: Unlimited and which highlighted many of the things that make the game fun. As for the foundational pillars of fun for Star Wars: Unlimited that we identified during Legends of the Force, we would end up bringing those forward into future sets to help inform the mechanics and cards we were designing and ensure we reinforce the play experience that we want from this game.

Intentional Experiences

While this article contains stories about specific cards and mechanics we designed for Legends of the Force, I wanted to use these stories to highlight a larger point: that when you're designing something for an audience other than yourself, it's important to think about what kind of holistic emotional experience you want them to have. We could have easily gotten bogged down by the specific metagame incentives of various iterations of the Force mechanic and latched onto whichever seemed like the most interesting mechanic in a vacuum, or we could have continued designing around a style of control deck that leans hard into removing every threat and grinding out an eventual inevitable victory, but neither would have gotten us to the designs that we ended up with. It was only by asking ourselves the hard questions of “what emotional experiences will make this game the most fun for our audience” that we were able to land on the mechanics and designs that we did, and I think Legends of the Force is some of the most fun gameplay we've designed to date because of it. If we're doing our job right, a lot of our design work should go unnoticed by the players—and that's what makes a look behind the curtain that much more interesting!

May you feel inspired to try something new.

Share This Post