Behind Unlimited: Designing for Draft

May 29, 2025 | Written by Tyler Parrott

To my money, draft and sealed are the most fun formats of any card game. They're skill-testing, asking you to figure out a strategy with suboptimal components. They're thematically satisfying, because it lets each environment double-down on a theme so that all the pieces are sculpted to create a single, coherent experience. And they allow every game piece to have a role, despite the fact that most cards aren't strong or synergistic enough to have a home in a constructed format like Premier. I love how draft environments often feel recognizably distinct from each other, using their different mechanics and card designs to make each set feel unique and memorable.

There's a whole category of player who mostly only engages with a trading card game through draft and sealed, whether because of preference or because they only play casually enough that the equalized starting point (of owning nothing) makes the game more accessible to them. Non-trading card games have attempted to create draft environments in the past, but those attempts have been impeded by the fact that they require someone to own the full card pool to supply the cards. Trading card games, on the other hand, have the advantage of coming in low cost, readily-accessible booster packs—the ideal way to produce a randomized experience with a limited card pool!

Therefore, when we set out to design a Star Wars™ trading card game, we knew from the beginning that it had to be designed in a way that would optimize the draft experience. We would be squandering one of the greatest strengths of the distribution model if we didn't. So, how did we design Star Wars: Unlimited for draft, and how does that format influence the individual card designs within a set?

Opportunity Costs

When players are making card selections in a draft, or when presented with a pool of cards for sealed play, they are, by design, working with limited tools with which to build their deck. This is one of the most exciting elements of the format, but it also means that scarcity is a foundation for the entire format. It means that every card has an opportunity cost that informs a player's choices: if they select a Hera Syndulla (Jump to Lightspeed, 45) to go in their deck, that might come at the cost of not including the Adept ARC-170 (Jump to Lightspeed, 114) in the same pack or sealed pool that their deck also needs. Understanding this relationship is crucial to designing a fun draft/sealed format.

At the same time, most players who participate in a draft or sealed event are not looking to be challenged with every decision they have to make. To those players, the prospect of every booster pack in a draft representing 14 equivalent game pieces can feel overwhelming, to say nothing of trying to build a 30-card sealed deck with 84 available cards. Having some cards be obviously more powerful than the rest is extremely valuable to those players, as it helps guide them towards a particular strategy. However, if those same powerful cards appear in every single draft or sealed event, then the variety that draws players to the format quickly vanishes and players are likely to get bored. Therefore, we try to ensure that the powerful, game-defining cards that players use are different at each event. We primarily use three tools to do so: rarity, aspect, and cost. As you might expect, all are interwoven with each other.

The first, most obvious, way to make a powerful card appear in fewer games is by making it literally appear less often in booster packs. Each pack contains nine Common cards, three Uncommon cards, one Rare/Legendary card, and one foil “wild card” of any rarity. When there are 9 times as many Commons as Rares, but only 1.4 times as many Commons in the entire card pool, it means any given Common is going to appear fairly frequently and any given Rare or Legendary is going to appear pretty infrequently. If the rare cards are more powerful than the common cards, then the most powerful cards a player sees in draft or sealed are usually going to be different from game to game. Rarity also can be a very effective communication tool: when a player opens a booster pack, if they know that the rarer cards are more likely to be stronger than the common cards, they don't have to think as hard about the common cards they probably shouldn't be selecting first for their deck, and can focus on the exciting Rares that they open to direct their deckbuilding decisions.

However, it was also important to the design team during the development of the game line that our Premier constructed format have as many viable game pieces as possible, and that meant having strong cards at every rarity. This is where the aspect system entered the equation. By design, the more aspect icons a card has, the less available it is to deckbuilders, and therefore the less frequently it appears in games. Even if every sealed pool were to receive the same powerful multi-aspect card, not every player would end up playing that specific combination of aspects, and its natural opportunity cost would prevent the card from becoming ubiquitous.

The same logic is true with a card's cost: if a powerful card costs more resources, then there are fewer rounds in a normal game where that card can be played. Just as before, even if every deck had a powerful 7-cost card in it, that card would be played less often than a powerful 2-cost card, and therefore the 7-cost card would feel less ubiquitous than the 2-cost card. Taken together, these three tools point toward a system where the powerful cards are generally more expensive, have more aspect icons, and/or appear less often in booster packs.

These tools are valuable for understanding how to ensure that a draft environment remains fun, but they only answer questions that relate to an individual card's design. What they don't address is how to create a system in which the power disparities between individual cards results in interesting drafting decisions. In order to create that system, we have a much larger, more intricate tool, one which addresses the structural needs of draft as a format. We call this a “set skeleton."

Flesh and Bones

A set skeleton is the mathematical foundation upon which a draft format is built. It helps direct designers toward ensuring the cards that players need to play the game actually appear within the system at the volume needed for players to have access to those cards.

For instance, if we want to ensure that players have equal access to all four main aspects (plus Heroism/Villainy), then we need to ensure that all those aspects are equally represented. If we want to ensure that players have access to enough cards of each cost for their deck, then we need to ensure that there are enough cards available at each of those costs. The way we sculpt the possible options available within any given booster pack goes a long way toward sculpting the player's experience with those cards when they sit down to play draft or sealed. After all, we want players to feel like they're playing against each other, not against the system.

Most of what I'm going to describe pertains exclusively to the Common and Uncommon cards within a set. When there's only 1 guaranteed Rare/Legendary card per pack, each player is only going to get, on average, about 4 Rare or Legendary picks, and they may not even be able to play them all. Therefore, the overwhelming majority of a player's available card pool will be made up of Commons and Uncommons. Given the relative scarcity between Commons and Uncommons, a player is much more likely to see any given Common than any given Uncommon, meaning that Commons serve as the format's building blocks and Uncommons serve as deck-defining cards that a player can have a realistic, but not guaranteed, chance of seeing in a given draft.

In a practical sense, I tend to think of the set's infrastructure as being equivalent to the infrastructure of an individual player's deck. This means I want the percentage of cards within the set, of each card type and at each cost, to be roughly equivalent to the percentage of cards that an individual deck would need. For example, if a deck is usually about 70% units, then we build our draft environment to be about 70% units (specifically, our sets generally have at least 75% of Commons be units and at least 66% of Uncommons be units). If players are drafting at the same skill level, all the basic building blocks of a deck should self-correct and fall to each player roughly evenly. The same is true of a set's cost curve: we intentionally design more units that cost 2 and 3 than any other cost, since every deck needs a critical mass of early-game plays in order to participate in a game in a satisfying way.

Within a set skeleton, aspect balance is critical. On a macro sense, all aspects appearing in equal amounts maximizes the variety of game experiences within a draft/sealed environment. If one aspect is overrepresented within a set, then players are going to naturally gravitate towards playing that aspect more often at the expense of the other aspect, and they'll find that their draft and sealed games lack the variety that makes the format so consistently enjoyable. On a micro sense, it makes it increasingly difficult for players during a draft to make guesses about what the other players around them are drafting, and thus it takes away a valuable strategic depth that enfranchised players enjoy. Humans aren't good at interpreting randomness, so having all aspects appear in exactly the same volume (at Common/Uncommon rarity) helps build player confidence in their own ability to make strategically viable decisions.

Taken together, the set skeleton begins to look like a mathematically predetermined infrastructure in which to fill in individual card designs. We can confidently predict that any given set will start with three Common cards and four Uncommon cards of each aspect combination (primary aspect plus Heroism/Villainy). We can be certain that each aspect will have exactly the same number of single-aspect cards, such that all aspects are equally represented, with the four primary aspects being balanced against each other and the two Heroism/Villainy aspects balanced separately against each other. We can expect that within a single primary aspect aspect, the units will range from 1 to about 7 cost, with the largest number of units within that aspect costing 2 or 3. We can expect 75% of the units at Common/Uncommon rarity to be ground units (except for Jump to Lightspeed!), and we can expect more events and upgrades to appear at Uncommon than Common.

From there, it becomes a matter of filling out individual designs. What kinds of cards do the new mechanics support, and where do they want to fit into the set skeleton? What deck archetypes is this set trying to introduce or support? Does the specific card that a designer has been trying to make actually fit into this set, or do the set's other needs crowd it out? Does a particular Common leader need certain support cards in order to function in draft?

Come to think of it, how do leaders fit into all of this?

Leader-Driven Infrastructure

Each set has eighteen leaders. Two leaders don't appear in booster packs, being Spotlight Deck leaders, and the other sixteen are usually separated into two sets of eight: each aspect combination has one Common and one Rare leader. The Common leaders, being the ones that overwhelmingly appear in draft pools, are designed and optimized for the draft environment while the Rare leaders, being mechanically weird or difficult to use, are designed and optimized for constructed formats. This leads both sets of leaders toward having different design priorities.

Consider the two draftable Aggression/Villainy leaders in Jump to Lightspeed. Captain Phasma is an aggressive leader whose ability requires you to include a lot of First Order cards in your deck in order to use her ability. Major Vonreg is a similarly aggressive leader, but he requires you to play lots of Vehicles to activate his ability. Both leaders require you to build your deck a certain kind of way, but in the Jump to Lightspeed card pool, there are a lot more Vehicle units than there are First Order units. Even if the First Order payoffs in Captain Phasma's deck are stronger, it's still very hard to get enough units of that trait in your deck, and the play experience of drafting with her could end up being frustrating or disappointing (even if you win). We want the experience of drafting Phasma to be an exciting challenge that a player opts into, not the default experience players are engaging with when they draft an Aggression/Villainy deck.

Major Vonreg, on the other hand, is fairly straightforward to draft for: a Pilot card's deck is going to want lots of Vehicles anyway, and they're plentiful in all of the aspects. Because there are enough Vehicle units available, the question Vonreg asks you is not if you can use your leader, but when and how. These are the kinds of exciting decisions that players are looking for when they sit down to play Star Wars: Unlimited: the strategy of how to maximize the cards they have, not hope that their cards will work in the first place.

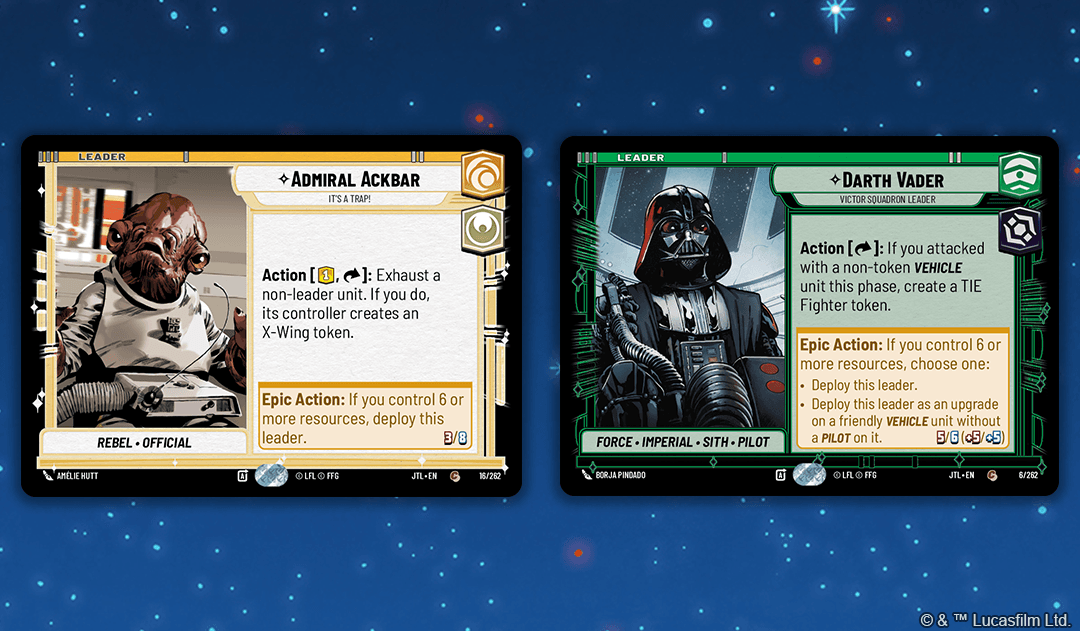

Given that, we often want our Common leaders to be more generally useful. Oftentimes this looks like pushing leaders toward designs that are either dependent upon the existing board state rather than their deck contents (like Admiral Ackbar), or ones whose deckbuilding restrictions are loose enough that there are plenty of options in all four primary aspects to explore (like Darth Vader and Major Vonreg). As a general rule, you'll find the Common leaders are easier to deckbuild for and skew more toward gameplay decisions than their Rare counterparts.

That said, there's still plenty of room for deckbuilding-focused leaders in draft. Grand Admiral Thrawn (Jump to Lightspeed, 2) is one who I personally fought against during the design and development process, as I was concerned that such a prescriptive design would be too difficult to deckbuild for in a draft environment with a limited card pool, especially since it would exclude almost all of the set's necessary simple Common designs. However, our set leads were committed to not just a “When Defeated”-matters version of Thrawn (which I figured was fine as a Rare leader), but also that he would be Common and a full draft archetype. To their credit, they were able to design enough Common and Uncommon units with desirable When Defeated abilities, and in enough different aspect, that my pushback proved needless, and Thrawn emerged as an entirely capable draft-focused leader.

This is, perhaps, not that different from other common leaders with restrictive deckbuilding requirements: Leia Organa (Spark of Rebellion, 9) and Grand Moff Tarkin (Spark of Rebellion, 7) in Spark of Rebellion, after all, required Rebel and Imperial units, Hondo Ohnaka (Shadows of the Galaxy, 5) in Shadows of the Galaxy requires units with Smuggle, and even in Jump to Lightspeed, there are leaders like Wedge Antilles (Jump to Lightspeed, 8) who requires units with Piloting or Luke Skywalker (Jump to Lightspeed, 12) who requires Fighter units. The key is that, whenever we design a deckbuilding-restricted Common leader, we do so while understanding the mechanical pressures these leaders apply to the entire set.

If a leader like Thrawn, Wedge, or Luke is a Common leader for a set, that set's skeleton needs to consider the mechanical requirements of that leader. Jump to Lightspeed needed a certain number of Common and Uncommon units with When Defeated abilities to ensure that Thrawn could be satisfying to play in draft, enough Piloting units for Wedge, and enough Fighter units for Luke—all before considering other things that the set might want, such as “is there the correct balance of ground and space units” or “are the Common units simple enough to be accessible to new players” or “are there enough units with crucial abilities, like Sentinel, that lead to fun gameplay”?

As you can imagine, with so many constraints on how a Common leader is designed, it can sometimes be difficult, even frustrating, to find a design that feels fun and satisfying to the designer's vision! I personally find such challenges fun and compelling, but even I have to admit that there have been weeks where I keep trying design after design, throwing each one out as it's either too narrow to draft for, too unthematic to the character, too broken in Premier, or just not exciting enough. But that's why we iterate as often as we do, and why the collaboration of the design team is so valuable!

Assembling the Pieces

In a lot of ways, designing for draft presents a lot of the same exciting puzzles and challenging quandaries as playing in one. There's so much interconnection within the entire draft ecosystem, and so many factors are pulling any individual card design in different directions at once, that figuring out the right combination of statistics, abilities, and theme for each card is like trying to assemble a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle without knowing what the final image is supposed to look like. Each iteration, just like each booster pack that gets passed around the table, shows you a slightly different picture of what the set wants and needs, and each decision you make informs each future decision you will make when building the system. Only, instead of creating a deck at the end, you're creating an entire game.

Hopefully this has given you a glimpse into what factors go into designing a game that's meant to be drafted, and why those factors are important. It continues to be a core element of our vision of Star Wars: Unlimited's gameplay experience, so you can bet we'll continue to explore ways to keep draft and sealed fresh, exciting, and fun as we move forward into Legends of the Force, Secrets of Power, and beyond.

May you feel inspired to try something new,

~Tyler Parrott

Share This Post