Behind Unlimited: A Theory on Agency

December 18, 2025 | Written by Tyler Parrott

Early last year, in the midst of a certain debate about game design principles with some of my fellow game designers, I realized I had been in that particular debate before, and with similar people taking up both sides of the topic. I began wondering why such a topic of dissent was consistent, and I have been keeping an eye out for it ever since. Given some of my observations, I would like to present a thesis about how players experience head-to-head card games and consider what it means in card design.

Comfort and Control

If you were to ask someone “why do you play games,” the most likely answer you're going to get is “to have fun.” After all, life is stressful, work is hard, and games are activities used for entertainment. If a game were to stop being fun, there would be no inherent incentive to play it (though in some cases external social or physical incentives can and do exist). So, as a game designer who wants players to keep coming back to my games, I have a strong incentive to make sure those games are fun. Unfortunately, what is “fun” is different for everyone, which means I have to make some judgment calls in the design process!

In the hierarchy of needs of “being a human,” comfort is one of the most foundational. If I want my players to have fun with my game, then it's important to me that they feel comfortable while playing that game. And one of the prerequisites for feeling comfortable is feeling safe. Now, games naturally exist in a safe space, but one of the primary incentives humans have to play games at all is that games stimulate emotions, and people like to feel things. That said, not all emotions are positive. It's entirely possible for a game to make a player feel a lack of safety, even if they wouldn't necessarily describe it that way.

This is what brings my thought process on player comfort to the topic of control. For most people, the experience of safety is derived from a feeling of agency. In the context of a card game like Star Wars™: Unlimited, this agency usually comes from “being able to make decisions that matter.” The fewer opportunities players have to make decisions, or the less the outcomes of those decisions matter (because they were invalidated by randomness), the less agency players feel like they have in the game. On the other hand, the greater the number of options available to players, and the more that players can immediately see the results of their decisions, the greater control they feel over the outcome of their game. I believe that one of the things that players love about this game specifically is how the increased volume of card draw and the resource selection mechanic both specifically make players feel in control of the strategy they want to employ with their deck.

Categorizing Frustration

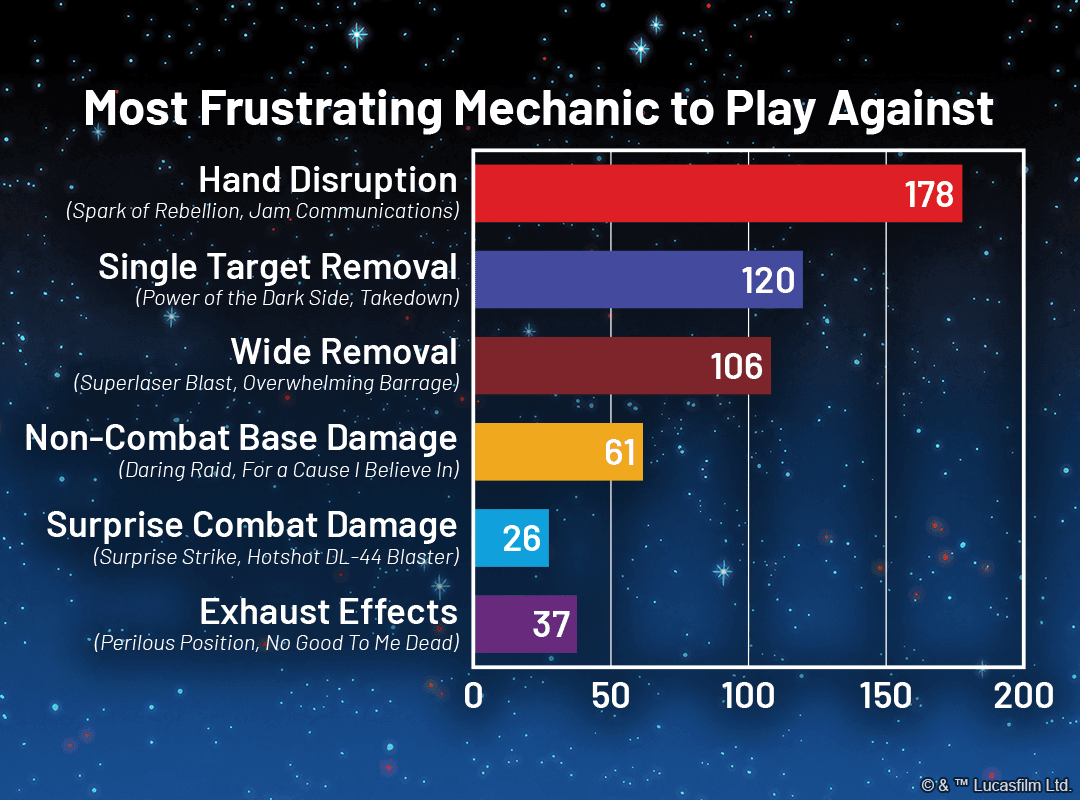

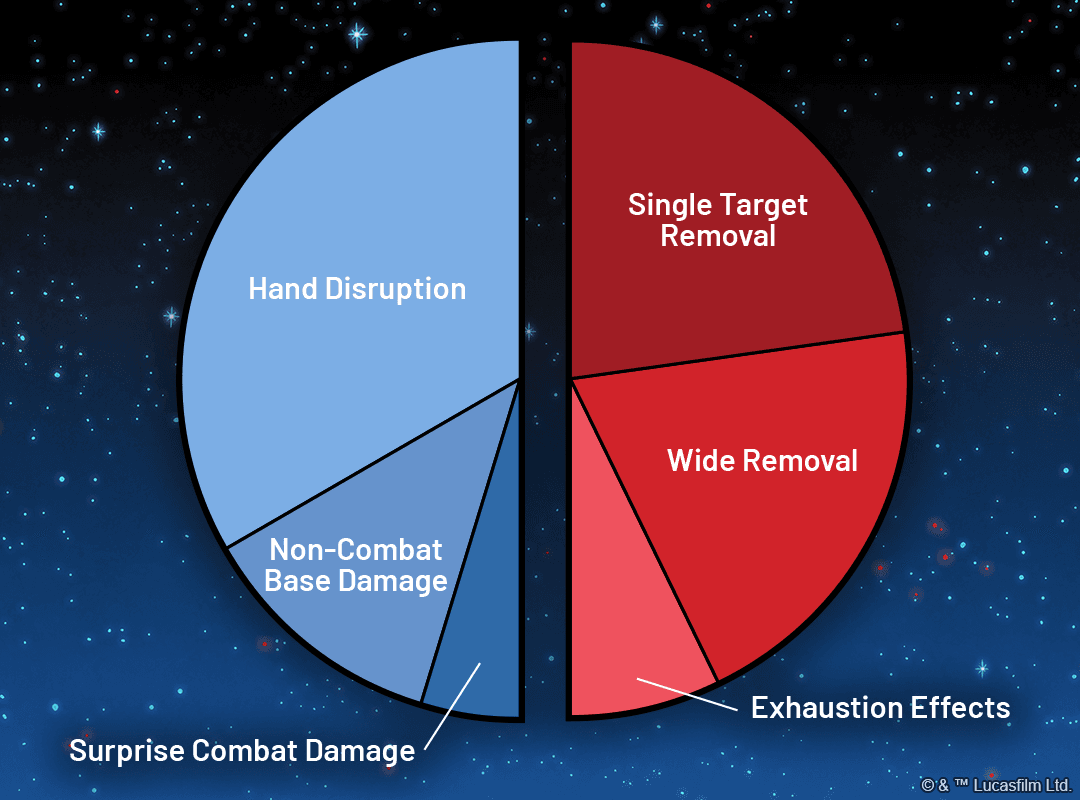

At the Galactic Championship this year in Las Vegas, we had a survey players could fill out to help guide our product design and game development behind the scenes. One of the questions we asked players was: “What mechanic do you find most frustrating to play against?” As you can see, we got some pretty clear answers:

To those who've played competitive TCGs for a long time, this may not come as a surprise: players don't like it when their cards get removed from the game. The most popular answer (33% of responses) said that hand disruption feels the most frustrating to play against, which makes sense as it prevents them from playing their cards. The second most popular answer (23% of responses) was single target removal, with another 20% identifying mass removal and another 7% identifying unit exhaustion as the most frustrating to play against. I would combine these three into a single category, as they all describe a frustration with an inability to use the cards they have in play. Importantly, this combined category makes up almost exactly 50% of respondents. The final ~16% of respondents all expressed frustration with abilities that end the game unexpectedly, which I would describe as a frustration with losing the game before they get to either play or use their cards.

While the frustration of removal is well-documented in TCG spaces, I think the frustration of an early game loss is often overlooked. It's something we see fairly regularly in playtesting, but it's difficult to know what to do about it. When two players sit down to play a game, one of them will almost always have the faster, more proactive deck (or will draw a faster, more proactive hand) and we don't want to punish players for advancing towards their victory condition. So why would someone be frustrated that their deck was slower than their opponent's, when that's a natural outcome of a zero-sum game? The answer, I believe, is in the concept of virtual card advantage that aggressive strategies often try to exploit. Without getting into the specifics of how it works (that could be a whole article itself), the basic idea is that if a player loses the game with 4 cards in their hand, then that is functionally the same as if that player was forced to discard 4 cards from their hand at the beginning of the game. Therefore, I would make the argument that the frustration players experience when they lose to a fast aggro deck is more or less the same frustration that players experience when their opponent removes cards from their hand with cards like Pillage (Shadows of the Galaxy, 181) or Charged with Espionage (Secrets of Power, 230). If the game ends before I get to play the card I built my deck around, then I'm frustrated because my opponent prevented me from playing the card in the first place, the same as if they took the card out of my hand during the game.

Given all that, I would look at this data and conclude that almost exactly half of the respondents experience maximum frustration when their opponent prevents them from playing their cards and the other half experience maximum frustration when their opponent prevents them from using their cards. This conclusion mostly aligned with my anecdotal evidence and further motivated me to consider why people would experience these frustrations differently.

Expectations and Experience

Fundamentally, frustration is an emotion people experience when reality doesn't match their expectations. If someone experiences a terrible hardship, but it's one that they expected to happen, they're already primed to accept that outcome and so their frustration is minimal. In order to better understand why people would experience frustration in a TCG, therefore, we will need to investigate what their preconceived expectations are about what that TCG experience is going to be like.

The understanding that players approach games with different expectations isn't new to the TCG space either. It's the foundational idea behind the existence of formats: if you want a strategic competitive experience, you can play Premier; if you want a more improvisational experience, you can play draft; if you want a social experience, you can play Twin Suns. But even within those formats there can be further diversity of expectations. If a player sits down to play a game with the expectation that both players are trying to win at any cost, then they might be frustrated by an opponent who just wants to play a thematic deck built around their favorite character (and vice versa). When there are so many reasons someone might want to play a game—be it for competition, for novelty, for self-expression, for storytelling theme, for socialization, etc.—it's no surprise that players might not always play against someone with the same expectations of what the game will be like.

Now, some of this experiential difference is inevitably going to be because the game is zero-sum: the winner of a game is naturally going to have a different experience than the loser will. But there are many individual things that can happen during a game that players can or will have differing feelings about, and understanding those feelings can better inform our understanding of player expectations. Consider the following examples:

- Both players play very aggressively, attacking each other's bases to get within the range of victory. One player has the upper hand, however, with more power on the board and a pivotal Pillage (Shadows of the Galaxt, 181) to remove all their opponent's backup options. The losing player claims the initiative, draws a Surprise Strike (Spark of Rebellion, 231) during the regroup phase, and steals victory from the jaws of defeat.

- How would you feel if you lost in this instance? The opponent won with a lucky draw outside of either players' control, which to many would feel unfair. Yet, they did also choose throughout the game to continue to attack the enemy base rather than try to stabilize from their losing position, setting themselves up for an opportunity to exploit a moment of good luck.

- One player builds a dominant offensive presence with their units on the board, but is unable to finish the game before their opponent plays Superlaser Blast (Spark of Rebellion, 43), wiping out their entire board and their leader with a single card. That player is unable to rebuild because of the Emperor Palpatine (Spark of Rebellion, 6) leader that hadn't been deployed yet, which allows the opponent to take control of whatever threat they put onto the board after losing everything.

- Does it feel fair for the Palpatine player to be able to invalidate their opponent's entire board and investment with a single event, or did that opponent fail to consider that Superlaser Blast was a strategic tool that needed to be avoided?

- On the first round of a game, one player plays an aggressive 2-cost unit while the other plays Spark of Rebellion (Spark of Rebellion, 200), looking at the opponent's hand and removing the only available 3-cost card from it.

- Is either player in this example being prevented from playing the game? Yes, one player can't play a unit on their next turn, but they do have a unit on the board that can attack while their opponent does not.

Situations like these led me to consider: do players have preconceived expectations about where and when they have agency during a game? And if so, could I categorize those expectations in ways that would allow me to analyze and predict how players might react to specific card designs?

Two Zones of Agency

My thesis is that players broadly fall into one of two camps:

- “Projection” players perceive the game as being one of secrecy and long-term strategy. To these players, the heart of the game is future-looking, where present decisions exist to support a future goal. These players feel a strong attachment to their long-term strategy, and therefore their sense of agency comes from their ability to execute the next stage of their ongoing plan. To these players, the cards in their hand are the most sacred and important: that's where the future of your strategy lives, and that's the part of your strategy that your opponent can't (usually) know about. These players are most concerned with playing the cards in their hand and understand that, once a card has entered play, it has crossed a prescribed threshold of interaction and is now fair game for their opponent to manipulate or remove.

- “Investment” players perceive the game as being one of present tactics and past commitment. To these players, the heart of the game is on the board, where they have invested the most resources (in card quantity and resource cost). These players feel a strong attachment to the cards they have in play, as they committed to playing these cards in the past and feel they deserve to get to use the cards they've spent resources on. When they don't get to use their cards, they feel like their opponent is denying them the ability to play the game. They're significantly less concerned with the cards in their hand being interacted with, because they haven't invested in those cards yet, and may not in the future as they change tactics based on new cards they draw each round.

The throughline for both categories of player—the reason that both experience frustration in different ways or contexts—is that both players have a different answer for what it means to be playing the game. For players in the “projection” camp, the game is fundamentally about choosing which card(s) you play each round, and the most important zone in the game is their hand of cards that's hidden from their opponent. For players in the “investment” camp, the game is fundamentally about choosing when and how to use their units, and the most important zone in the game is the two arenas where unit combat occurs. Neither camp commits to this perspective entirely (after all, you can't win the game just by playing cards, and you can't attack with units until after you play them), but this split identifies where the players feel like they have the most agency, and where they are the most frustrated when disrupted.

One might look at this conclusion and ask, “is there a way to avoid frustration for both types of players?” And the answer is yes! But it would come at too high a cost. We could certainly design a game that had no abilities to remove resources from the opponent, with no immediate unit removal and no hand or resource disruption. However, these kinds of abilities inject a critical uncertainty into the outcome of any given game, and they're necessary for the kind of metagame variety that a lifestyle card game needs to thrive (not to mention the fact that there's a whole swath of players who enjoy playing control decks). Without disruption, whichever deck built the biggest engine or the fastest board state would win nearly every game, and the player who got a slower start would never be able to catch up and turn the tables on their opponent. While a card like Superlaser Blast is extremely frustrating for investment players, it's a necessary tool for late-game decks to stabilize and turn a losing position into a winning one. And vice versa, Spark of Rebellion may frustrate projection players because it interrupts their ability to execute their strategy, but it's also necessary to prevent those strategies from becoming too consistent and thus the game becoming too predictable.

While it can be useful to understand what kinds of cards frustrate different kinds of players, I believe it's equally valuable to understand why other kinds of cards don't frustrate players as much as might be expected. I find it fascinating, for instance, that while Projection Players feel protective of the cards in their hand, they often don't extend that attachment to the cards that they've invested to the board. I've found that these kinds of players perceive a kind of unspoken agreement that interaction between the players is meant to occur on the board. They understand that they're playing a zero-sum game, but that losing access to their cards should only be done based on when and where they choose to play those cards. Thus, they perceive the execution of their strategy to be in the process of playing cards from their hand, after which they relinquish most of their expectations about what those units will or will not be able to do. In other words, to these players, the decisions that matter are the decisions they make with the cards in their hand because everything that happens to the cards outside of their hand is also outside of their control.

Just as projection players perceive their in-play cards as being somewhat beyond their control, I've found that investment players perceive their cards in the opposite way. It's the cards that are in play that they're most protective of, as those are the cards they chose to spend their limited resources on, and the cards in their hand are options for the future. Even investment players who have a pre-planned strategy still tend to have an underlying expectation that, because no strategy survives first contact with the enemy, the cards in their hand are just as vulnerable to interaction as the cards in play. Thus, they're sometimes more willing to accept hand disruption that's done to them than on-board removal, because the cards in their hand are just as much a part of the game as their in-play cards are, and if the opponent is going to mess with them then that opponent might as well take away the ones they haven't spent resources on yet.

This presents us, as game designers, with something of a challenge: if we want to have plenty of interaction in Star Wars: Unlimited so that games can remain dynamic and unpredictable, we can't commit entirely to only having on-board removal or to only having in-hand removal. One of the features of being a TCG is that we make a wide variety of cards for a wide variety of players, and while we want to minimize frustration for our audience, the kinds of cards that some players find fun will naturally clash with the expectations that others have for their gameplay experience. As a self-described investment player, I love using cards like Sabé (Secrets of Power, 17) or Lothal Insurgent (Spark of Rebellion, 190) to disrupt my opponent's ability to plan their turns even though I know it comes at a cost, just as cards that others enjoy, like Takedown (Spark of Rebellion, 77) or Topple the Summit (Secrets of Power, 183) can frustrate players like me who want to use the units that they have in play. As a game designer, I can't prioritize my own preferences over others because I want my game to be appealing to as wide an audience as possible.

In Understanding Frustration

This dichotomy that I've described, highlighting player attitudes that experience their sense of agency in different ways, could easily be summed up as “some players believe the game is primarily about playing cards from their hand and other players believe the game is primarily about using their cards in play.” But as with any generality, vanishingly few players will fall perfectly within one category or the other. We all have some facets of both projection players and investment players, even if one is usually more pronounced than the other.

Ultimately, my goal with this article is to highlight a recurring pattern I've seen among players and hopefully get you thinking more deeply about how you and others engage with the cards you play. After all, games are meant to be fun, and tabletop games especially are meant to be social. If these concepts help players understand a little better where each other is coming from, then hopefully some additional empathy will result in everyone having more fun in their gaming experiences.

Until next time, may you feel inspired to try something new.

Share This Post